Insights

Periodic insights from our Investment and Private Client Teams on a broad range of investment and advice-related topics

Published by the Private Client Team at KJ Harrison Investors

KJ Harrison Investors over the years has refined its views on financial and investment planning—views that it believes to be straightforward, actionable and measurable. In this paper, we discuss these philosophies and beliefs.

Many people believe that financial planning is a complex, highly technical process that magically produces desirable results. Viewed from afar, it can appear intimidating, confusing, and, in some cases, boring. But our thought is different. Planning is an area that you can control and comprehend—while producing peace of mind. A clear understanding of financial management is the logical starting place for taking ownership of your financial goals.

In simple terms, strategic financial management means setting a strategy with short- and long-term goals, developing a plan to achieve such goals, and monitoring the performance of that plan. It is a process relevant to all ages and all financial circumstances.

There exist three cornerstone concepts that are key to our views: generating free cash flow, formulating an investment matching strategy, and determining a risk management policy.

Free Cash Flow: The Essence of a Financial Program

The most important component of financial success, for either a business or an individual, is to generate free cash flow. From a business perspective, free cash flow is the profit or money that remains after all expenses are paid and after an appropriate amount is set aside to maintain current product capacity. Internal growth and financial flexibility are absolutely dependent upon free cash flow. And we believe that the same holds true for individuals. As in the case of a business, it is not enough for you to simply meet current expenses. On the contrary, you need to set aside funds for future liabilities, such as retirement. But, for this to occur, you need to have organized principles.

We all know people who earn a lot and spend it all. We also know that these people are not “profitable,” so to speak, and they are not building a sound financial foundation. It is essential to have adequate savings that can support you in the case that you’re unable to continue working. (We stress this particularly to clients in highly cyclical businesses, such as investment banking, and to professionals with potentially shortened careers.) As individuals or families, we should strive to produce free cash flow—from our occupations, or from our financial or other income-producing assets—after all personal expenses. For the record, “I’ll save what I don’t spend” is not a plan. It simply does not work; without discipline, expenses expand to income level. The necessary first goal, then, is to understand your expenses and to do your best to spend less than you earn. You need a savings goal that is realistic and achievable.

The power of free cash flow is incredible when demonstrated mathematically. An individual who begins saving $15,000 per year at age 30, and earns 7% per annum by age 65, will have $2 million; that same individual saving only $5,000 per year would have $691,000. Clearly, a successful savings program creates greater financial flexibility.

Free cash flow has another significant benefit: it reduces the pressure to overreach for investment return, which, as an outcome, makes managing the assets an easier task. We have seen too many individuals push portfolio risk beyond a reasonable level, due to the lack of savings. Inevitably, this leads to bailing out of a sound investment program during a poor market period, because the individual was in no position to accept market volatility and the periodic negative returns that equities can present. It is akin to a Las Vegas experience. Doubling down in the face of bad odds, in the hopes of hitting the jackpot, just isn’t prudent and, generally, isn’t profitable.

For almost everyone, the day will come when they retire or sell their

businesses—a time at which free cash flow from operations will end. If your investments or portfolios have been well managed, though, you can continue to generate free cash flow, in the form of dividends and capital gains, that is in excess of living needs.

If, at retirement, this is not the case, and the portfolio is heavily encumbered by living needs, investment managers will generally need to lower the volatility. Naturally, people become more conservative when they are no longer producing free cash flow—and financial professionals need to be very mindful of this. Income from more predictable sources such as bonds takes priority, often at the expense of capital growth. Meeting living expenses from unpredictable sources, such as stocks, is distressing and can be financially damaging in the longer term. This is particularly true if one is obliged to sell at an inopportune moment for the express purpose of meeting day-to-day cash-flow requirements.

We do not care how wealthy or how stretched you are. The core of good planning is generating free cash flow. By developing savings objectives and controlling expenses, you can lay the groundwork for a solid financial future. However, it takes considerable discipline and a well-considered plan to ensure that you remain committed to generating free cash flow. In all circumstances, it is critical to develop accountability to the plan. This, in turn, will ensure that spending is in line with objectives.

Once we have developed a plan to produce free cash flow (and we have taken appropriate steps to protect it), it is appropriate to discuss a reinvestment program. There are several opportunities that put free cash flow to work. Here are a few:

- Reinvest in opportunities relating to your business (this often includes paying down debt in the company first)

- Invest in other synergistic growth opportunities in your business

- Invest in real estate/income-producing assets

- Invest in financial assets, such as stocks, bonds, etc.

The first two opportunities can be very profitable and healthy, particularly in the early stages of a business. However, that changes once a business is well established. In this case, diversifying the risk associated with a single business—i.e., investing in a program that is relatively unrelated to your own business—is smart.

If part of the strategy is to invest in a financial program, you must first decide whether to outsource all or part of the investment program. Implicit in managing the assets yourself is having sufficient skill, experience, time, and resources to devote to the portfolio. In essence, you should think of your assets as a small business. If you owned a small business and were attempting to build it, you wouldn’t expect success based on a part-time effort. Similarly, if you do not have the resources, time, or interest in conducting a full-time effort, then professional portfolio management is your alternative. You need to think of yourself as the CEO of the financial program, with various executives to execute the program. A professional investment manager, then, is one of those executives.

If you decide to hire a professional investment manager, the task is to find one that fits with your objectives and style. The following factors should be considered:

The firm’s investment philosophy. Does the manager focus on a particular investment style? When does the manager’s style work well and when does it not? Does the manager perform over a full investment cycle?

The firm’s experience. How closely does the manager’s performance experience match their investment philosophy? Can they articulate how their performance experience relates to general market performance (i.e., do they do better in bull or bear markets, and why)?

The size of the firm. This has implications for how a firm views its clients and investments. Larger firms, by virtue of their size, tend to have performance reflective of the general market. Smaller firms, not restricted by their size to participate in a wide variety of investment opportunities, may have performance decidedly different from the general market. Larger firms tend to offer more, but standardized, products; smaller firms can often provide more customized programs.

Types of investments. Some firms specialize in only certain asset classes, while others are generalists participating in a broader set of asset classes. You should consider a plan to diversify the portfolio when hiring specialty managers.

The communication program. You’ll want to assess how a firm communicates with its clients. Some firms provide minimal communication and information about their investments (e.g., hedge funds, given the nature of their investments); others will communicate regularly and transparently. Ask for a sample client communication program.

Above and beyond this, you need to develop a strategy for a reinvestment program that is predicated on investment matching and risk management.

Investment Matching

Investment matching is choosing the appropriate asset structure given the time frame and objectives of the assets. There are two considerations for investment matching:

Rates of Return and Volatility

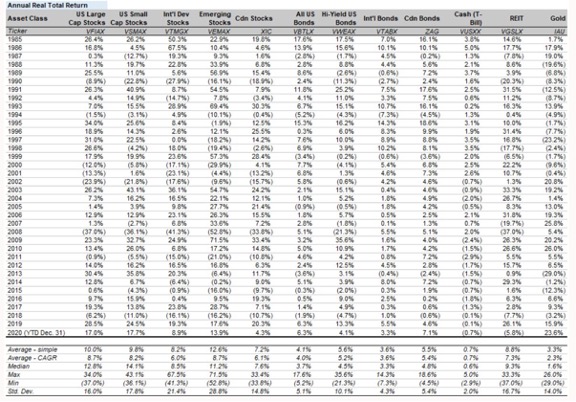

Each asset class is susceptible to varying degrees of volatility—and this has significant implications on planning. Provided is a summary of long-run returns of various asset classes and inflation. It is evident that, over time, shareholders have outperformed bondholders. This is intuitive. Otherwise, why assume the risk associated with stocks?

To earn higher average returns, you must expose yourself to higher fluctuations and risk. There are no “free lunches” in financial markets.

**Standard Deviation (Std. Dev.) is a statistical measure of volatility. The lower the standard deviation, the less volatility there is of single-year returns around the average.

Time Horizon

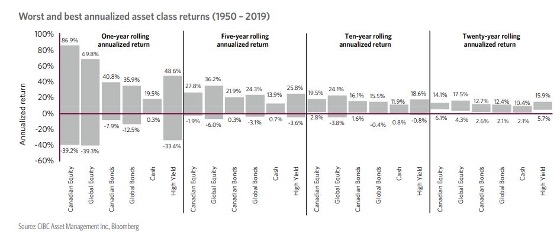

The first course of action is to determine the time requirement for the money. If the money is not needed in the short term and is being set aside for growth over the longer term, assets often characterized as “risky” become compellingly attractive, from both the risk and return perspectives. The following chart illustrates S&P 500 Index returns over different time horizons.

Market Risk is a Function of Time

As evidenced, the longer your time horizon, the less risky some assets, such as stocks, become. In fact, over an extended period of time, “more risky” assets experience greater upside with less downside than other assets considered “less risky” (e.g., Canada Long Bonds). An interesting analogy—and factual support—for this concept is the life insurance business. In the case of whole life policies, insurance companies will invest the proceeds in stocks. The return difference between the policy rate and the rate of return on the stock portfolio creates a profit. On the other side of the coin, for a GIC contract, an insurance company will match the term by purchasing a mortgage bond, where there is downside protection and a match to the term of the policy.

Risk Management

If a picture speaks a thousand words, and if we can see that stocks are the preferred long-term route, then why haven’t most people done well? In our view, the biggest risk to the financial asset program is that people do not tolerate losses well—specifically, those periodic losses that occur by simply owning stocks. Even over five-year periods, you can lose money.

In bull markets, everyone can afford to have a long time horizon. But, in a bear market, we observe that people’s time horizons shorten dramatically. Likewise, we find that long-term perspective goes out the window at the most inopportune moment. Even if stocks are the mathematically suitable match, the psychological pressure of a loss is difficult for many to accept.

With this in mind, we would recommend a more conservative approach, which will ensure adherence to a well-conceived financial program. An investment program that mitigates losses has a much better chance of ensuring that, during difficult times, one can maintain the long-term perspective.

At KJ Harrison, we strongly believe that our primary job as an investment counsellor is to manage the negative tail in the one-, three, and five-year periods. This will ensure that you don’t lose money—money that can take tremendous skill and time to regain.

Risk Control is a Function of Management

We also believe that financial success is very achievable. And that the key to ensuring this success is a well-designed plan. It need not be a daunting exercise. In fact, developing such a plan is liberating. It offers a sense of control; it allows you to understand the various outcomes and make sound decisions based on those outcomes. What is required is straightforward:

- develop a free cash flow plan with measurable goals;

- develop a reinvestment plan, which takes into account your time horizon and risk tolerance, for that free cash flow;

- ensure against straying from the plan by paying attention to investment matching and risk management.

Needless to say, a sound financial plan will provide peace of mind. After all, a disciplined approach automatically increases your odds that the financial wind remains at your back!

[1] https://themeasureofaplan.com/investment-returns-by-asset-class/

[2] https://woodgundyadvisors.cibc.com/documents/519163/519227/CIBC+Long-Term+Asset+Allocation%2C%20February+2020.pdf/5a538feb-68f6-45f2-848b-65b70a48fb7e